4

That old monkey business

You’ve heard the story, I’m sure.

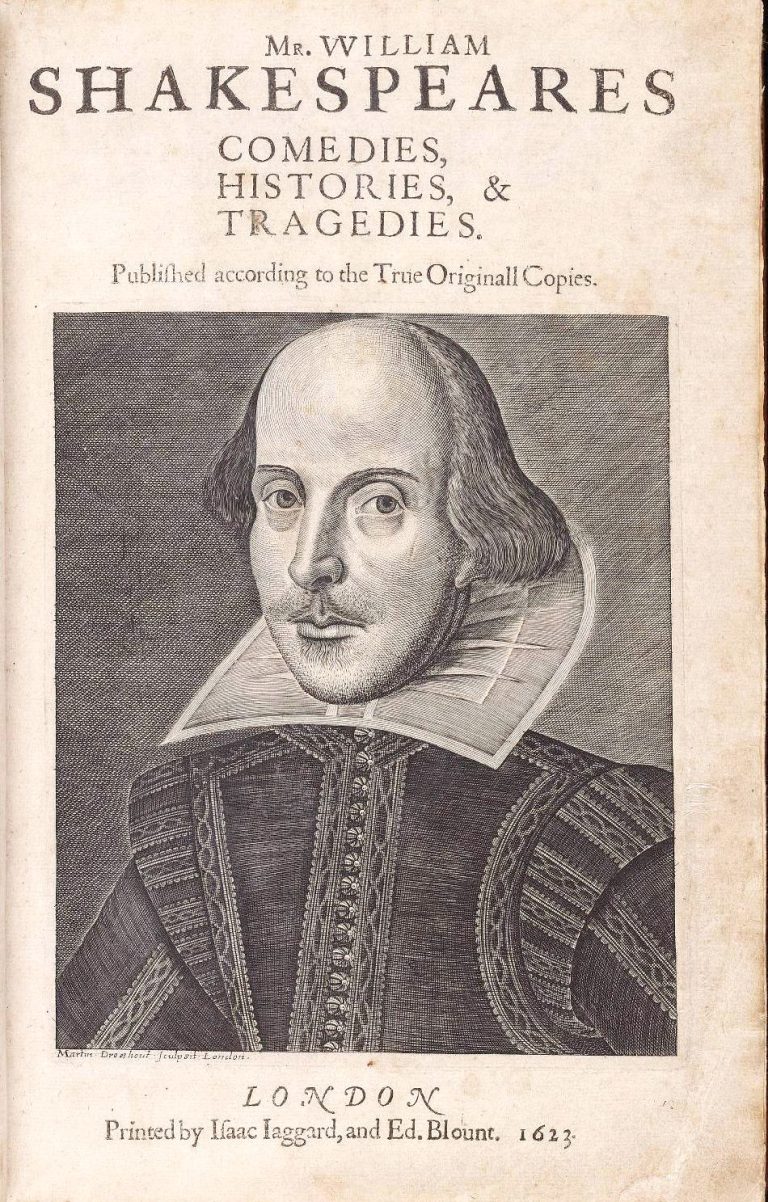

If you have a lot of monkeys typing away on lots of typewriters (or ipads), eventually, given enough time, they will type out the complete works of William Shakespeare – or 'Hamlet' at the very least!

The point of the story? That given enough time, anything can happen – that even the most complicated, unlikely thing we can imagine, like perhaps the living cell, could happen entirely by accident.

On the face of it, this sounds reasonable enough, and it has passed into popular culture in all sorts of ways. The story has been around a long time and recently a number of people have checked out the maths and worked out the actual probability involved. The results are very interesting. The maths are in essence quite simple but produce some very large numbers indeed.

If you have a keyboard with just 26 keys for the 26 letters of the

alphabet, the chances against hitting one particular letter by

accident are 26 to 1; there are 26 possible options, only one of

which is correct. The chances against hitting two specific

letters are 26 x 26 or 676 to 1; three letters is 26 x 26 x 26 or

17,576 to 1; and so on.

So what are the chances of getting some Shakespeare?

Let’s be a bit less ambitious: how about just one sonnet, a short poem, rather than the Complete Works?

Israeli physicist Gerry Shroeder writes:

‘All the sonnets are the same length. They’re by definition fourteen lines long.

I picked the one I knew the opening line for: ”Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” I counted the number of letters; there are 488 letters in that sonnet. What’s the likelihood of hammering away and getting 488 letters in the exact sequence as in “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day”? What you end up with is 26 multiplied by itself 488 times… or, in other words, 10 to the 690th." (note: these calculations don’t allow for the need for spaces between words or punctuation of any sort).

One followed by 690 zeros. That is what 10 to the 690th means.

One billion is 10 to the power of 9 – one followed by 9 zeros – 1,000,000,000. Do you have the faintest idea how big a number one followed by 690 zeros is? Is there perhaps another big number we can compare it with? Gerry Shroeder again:

‘Now the number of particles in the universe – not grains of sand, I am talking about protons, electrons, and neutrons – is 10 to the 80th – one with 80 zeros after it. 10 to the 690th is one with 690 zeros after it. There are not (not even close! ) enough particles in the universe to write down the trials…’ quoted by Prof. Antony Flew, author of ‘There is a God’ 2007.

Various ways of getting round this conclusion have been publicised, but all involve intelligent intervention – such as selecting each short segment that happens to match the target text and then assembling them together to match the complete text. Evolution of course has no such short cuts – no intelligence allowed.

Others have approached the problem from a slightly different angle: how long would it take to acheive this formidable task?

"If the monkey could type one keystroke every nano second, the expected waiting time until the monkey types out Hamlet is so long that the estimated age of the universe is insignificant by comparison... this is not a practical method for writing plays." Gian Carlo Rota

What seems on the face of it to be a piece of unremarkable common sense, is in reality complete nonsense. A story which was designed to prove one thing in fact proves the absolute opposite. Some mathematicians regard anything above 1 chance in 10 to the 50th as in effect zero probability: it’s never going to happen, ever.

For the record, the text of ‘Hamlet’, just one of Shakespeare’s plays, has not 488 but well over 132,000 letters.

In his book 'God's Undertaker', John Lennox quotes the astrophysicist Chandra Wickramasinghe:

"No matter how large the environment one considers, life cannot have had a random beginning. Troops of monkeys thundering away at random on typewriters could not produce the works of Shakespeare, for the practical reason that the whole observable universe is not large enough to contain the necessary monkey hordes, the necessary typewriters and certainly not the waste paper baskests required for the deposition of wrong attempts.

The same is true for living material. The likelihood of the spontaneous formation of life from inanimate matter is one to a number with 40,000 noughts after it... it is enought to bury Darwin and the whole theory of evolution. There was no primeval soup, neither on this planet nor on any other, and if the beginnings of life were not random, they must therefore have been the product of purposeful intelligence." 'Evolution from Space'

Sadly, he preferred the idea of life being seeded on earth by intelligent aliens ('panspermia') rather than admit a divine creator.

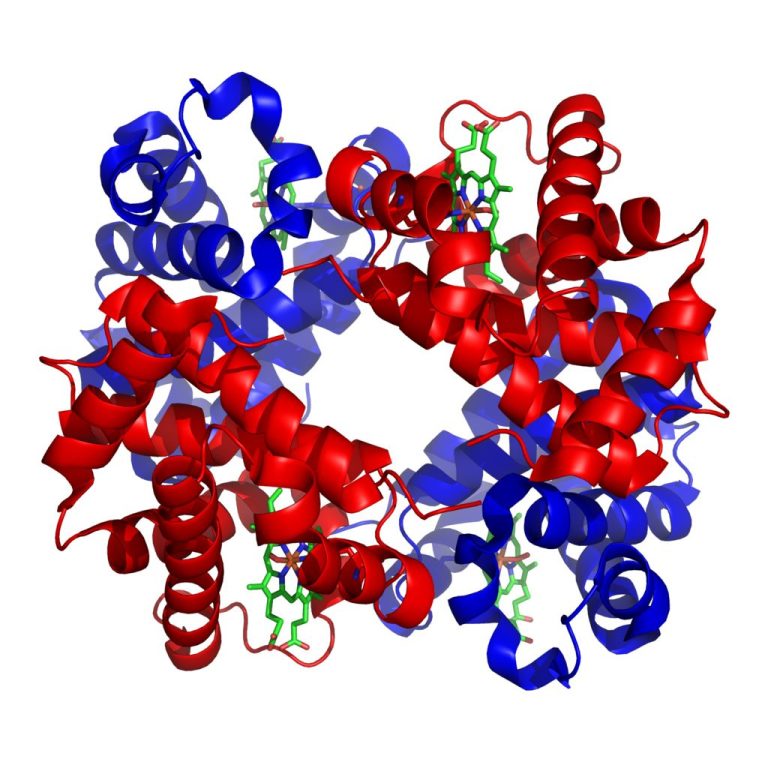

The real question of course is not about the possible productivity of hordes of mythical monkeys, but the likelihood for example of a single molecule of the protein haemoglobin assembling itself by chance. The odds against arranging the 20 amino acids involved in 4 chains each 146 links long is about 10 to the power of 170 – so says Isaac Asimov.

Some trace the monkey story back as far as 1860, to a famous encounter between Thomas Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, when Huxley championed the newly-minted theory of Charles Darwin. Why is this same old story still around today when it has been entirely discredited?

Why? Because the materialist culture of our times demands that life happened by accident – without design, without intelligence, without purpose. Millions pursue an ideal of absolute personal freedom which does not permit recognition of a supreme power to which they may be responsible. They are prepared to embrace the most fantastic degrees of improbability rather than admit the need for a Creator (see Footnote HERE).

REFERENCE: 'God's Undertaker' by John C Lennox

The 3D structure of the protein

haemoglobin.

To function, proteins need to have the

right 3D shape as well as chemical

makeup.

Haemoglobin is the vital oxygen -

bearing component of the blood. It

is common to all vertebrates apart

from the fish family Cannichthyidae.

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.