2

The accidental brain

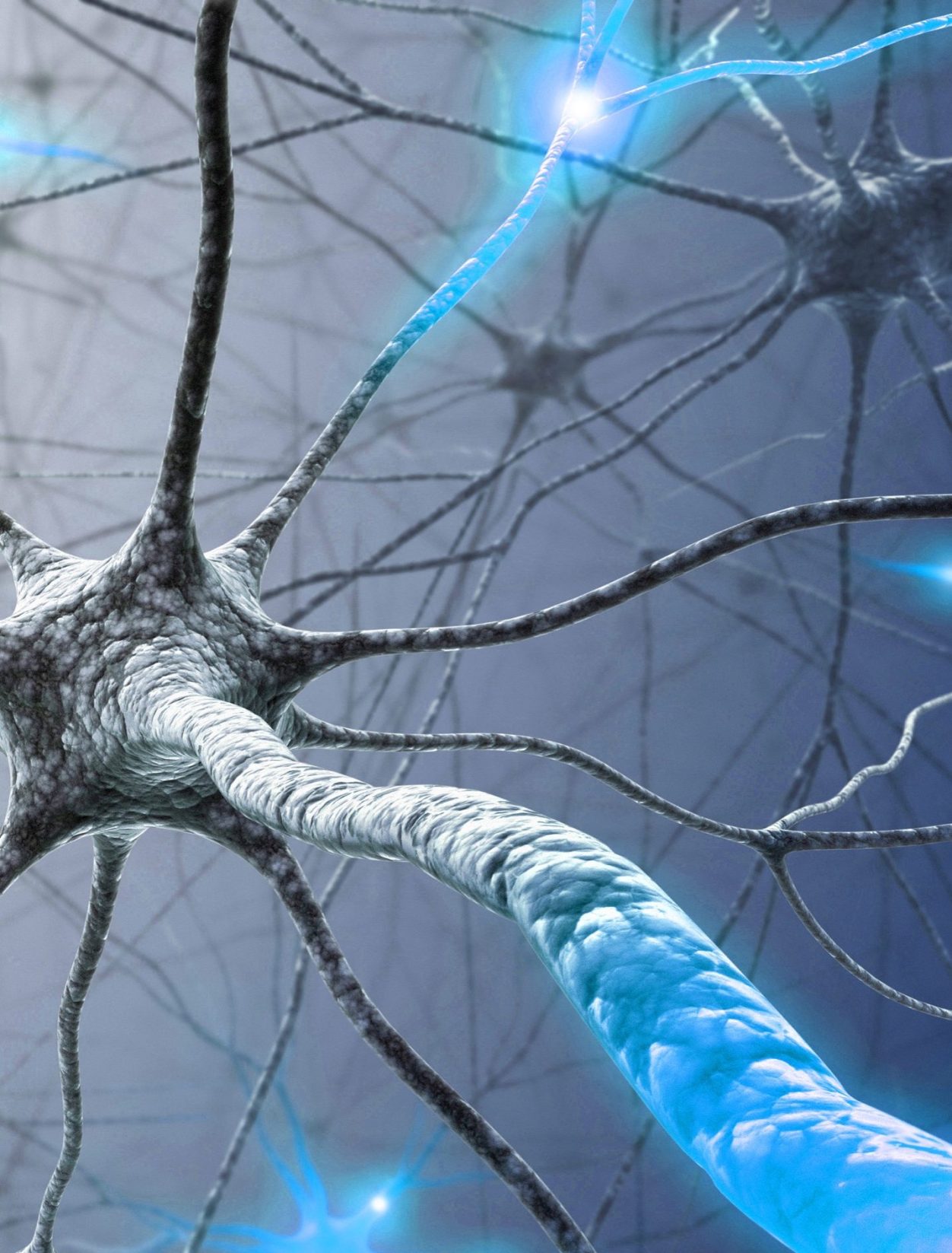

Inside the brain: artist's view showing interconnected neurones and multiple signal pathways.

Our brains can sometimes be frustrating.

A well-known name, the password or pin number we have used a thousand times, sometimes they vanish into thin air at the most embarrassing moment. But generally, we have the impression that our brain is quite amazing, though we may not have much idea about how it works.

The picture above shows an artist’s impression of a small part of the human brain. The large objects that look like satellites are ‘neurones’, and they are connected to each other in various ways by what look like cables or wires.

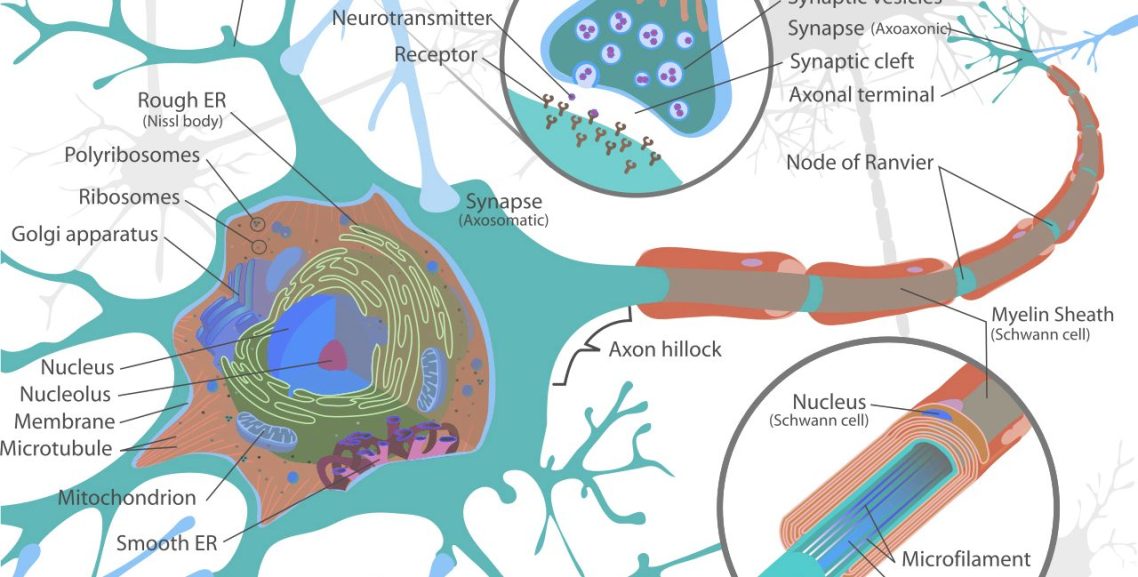

Neurones are the most important component of our brains, the ‘grey matter’ as we call it. A neurone is a nerve cell, the basic building block of our nervous system, designed to process and transmit information (in a chemical or electrical form) throughout our bodies. If we call them microprocessors, we would not be far from the truth. There are several different types, e g ‘motor neurones’ transmit information from the brain to the muscles of the body, to trigger the action which may be needed.

Detail of a single motor neurone

The cables in the picture are ‘axons’ which link the neurones together and enable them to talk to each other. They are covered with a whitish fatty deposit (myelin) that protects the signals from interference, rather like the insulation around an electrical wire. The axons account for most of the ‘white matter’ deeper in the brain’s structure. So, the brain is like a big communications hub or exchange, handling minute coded signals, identifying, processing and sorting them, sending them to different parts of the hub and storing them when required.

How much of the brain can you see in the picture above?

The neurones are easily identifiable and I can count about five of them but how many are there in total in your brain?

One hundred billion.

100,000,000,000

Each of those one hundred million neurones is connected to about 10,000 others in a vast network. This is comparable in complexity to the whole of the world wide web.

"The most complex piece of matter in the universe", so far as we know – that is how the brain has been described. And it will remain that way until we discover the fabled ‘aliens’ who might even have made us themselves, according to popular mythology and even a few serious scientists.

So-called ‘accepted wisdom’ tells us that this astonishing apparatus is an accident, the end result of several billion years of the creative mistakes that are called ‘evolution’. Everything that can be attributed to our brain, the capacity for rational thought, the laws of language and logic, the science of mathematics and everything else, is likewise the product of chance and essentially purposeless.

In 2004 Norman Geisler and Frank Turek wrote a book called ‘I don’t have enough faith to be an atheist’ (published by Crossway). Their argument was that atheists who so often pride themselves on not requiring faith of any sort, in fact subscribe to a whole series of propositions that have no scientific basis. Their belief in them is a matter of faith – faith in a particular materialistic worldview that excludes divine action.

I think Geisler and Turek are absolutely right. It requires a lot of faith to believe that the human brain is the product of chance, and I do not have it. I do not understand how anybody with moderate intelligence and a healthy dose of common sense, can possibly believe such a thing, unless they are already determined they ‘cannot allow a divine foot in the door,’ as one biologist puts it (Richard Lewontin – see footnote at bottom of this page).

Our brain in action – an example

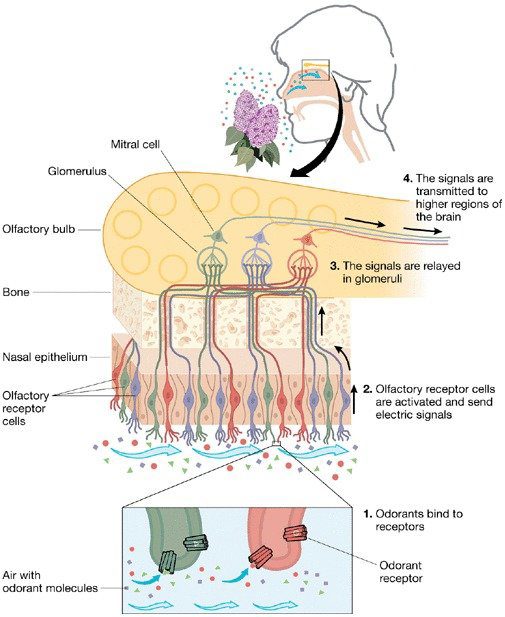

Perhaps the least tangible of our senses is our sense of smell. Scent is elusive, it seems to defy analysis. We cannot collect it or preserve it with a photo or a recording, we cannot describe it except in terms of other scents that we have stored in our memory. An airborne particle of matter is drawn into our nostrils and encounters the tiny hairs (cilia) in the top of the nostril. These are attached to ‘receptor’ cells (about 12 million of them) which generate a signal specific to that molecule and pass it on to the axons. Several thousand axons bundled together like a multi-strand cable make up the ‘olfactory’ nerves, one from each nostril, which connect to a bulb on each side of the frontal lobe of the brain. There, the ‘magic’ of data processing produces in our consciousness that elusive sensation which we call smell. It is said we can identify up to 10,000 different smells. But that is just the beginning.

Our sense of smell

Karolinka Institulet and Nobel Foundation

Through this amazing network of communication, other parts of the brain are alerted to the same information and trigger a number of different responses. A smell may bring back memories from the past, a trip to Africa, a place from our childhood, a particular person, or a special incident. In a different part of the brain, it may stir a range of emotions, from love to fear and disgust. The smell of burning or gas may trigger panic and a flight response designed to place us as far from the source of the smell as possible. Meanwhile other parts of the brain continue to maintain and control the body's vital signs, its temperature, blood pressure, hormone balance etc etc. In this way different specialised areas of the brain all respond in different ways to the same tiny signals.

Is it really possible to believe that all this is accidental? It may be a convenient explanation that avoids the embarrassment of acknowledging a Creator, but do we truly believe it? Doesn’t our intuition, our common sense, our experience of life, all tell us the opposite? What would Darwin himself have thought if he had known a fraction of what we know today? He could see that a highly specialised organ like the eye was a problem for his theory. What would he have to say about a computer operating system (OS) controlling 100 billion microprocessors, a few pounds of grey matter that rivals the entire world wide web in its complexity?

THE WORLDWIDE WEB

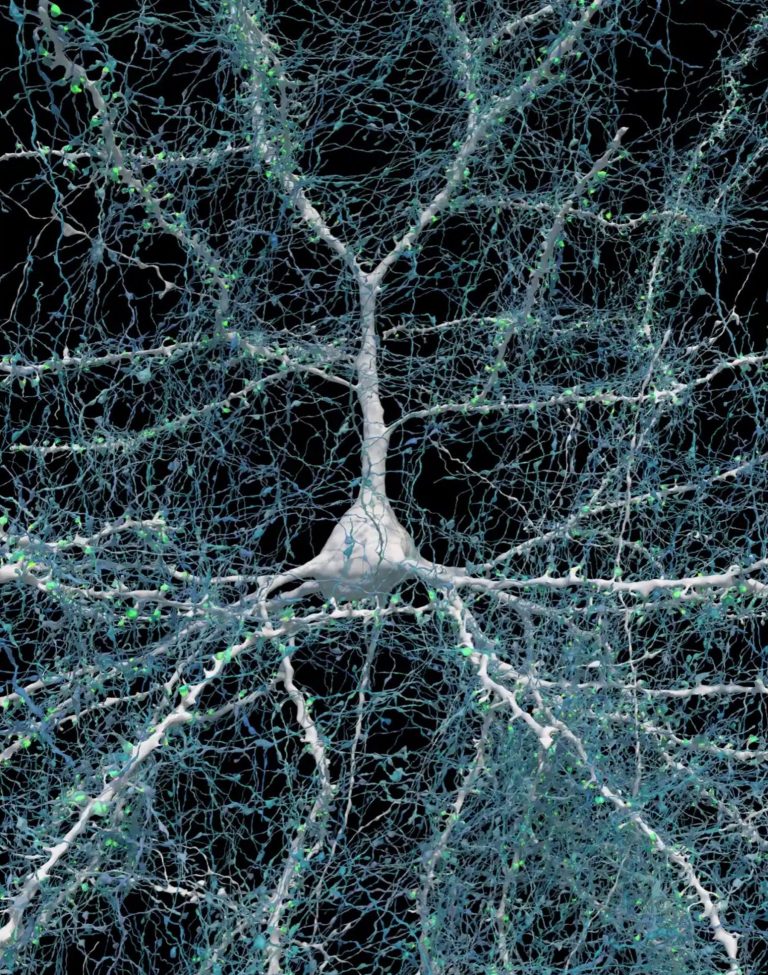

UPDATE 10 May 2024 the English Guardian newspaper reported on research announced in Science Magazine, an unprecedented study of one cubic millimeter of the human brain – see HERE

The picture on the right is not an artist's impression. It is the result of electron microscope images of 5,000 slices of the sample.

ILLUSTRATION: D. Berger/Google Research & Lichtman Lab

(Harvard University)

Footnote:

The following is a quotation from an atheist biologist who is unusually honest about the ‘mindset’ of many contemporary scientists:

"Our willingness to accept scientific claims that are against common sense is the key to an understanding of the real struggle between science and the supernatural. We take the side of science in spite of the patent absurdity of some of its constructs, in spite of its failure to fulfil many of its extravagant promises of health and life, in spite of the tolerance of the scientific community for unsubstantiated just-so stories, because we have a prior commitment to materialism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, we are forced by our… adherence to material causes to … produce material explanations, no matter how counterintuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a divine foot in the door."

Richard Lewontin, Harvard University

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.