8

Take a deep breath

jitendrajadhav/ istock

Almost every form of life on earth depends on the oxygen that makes up nearly 21% of the earth’s atmosphere (how did that happen?!). Each organism has different ways of extracting oxygen from its surroundings, whether air or water.

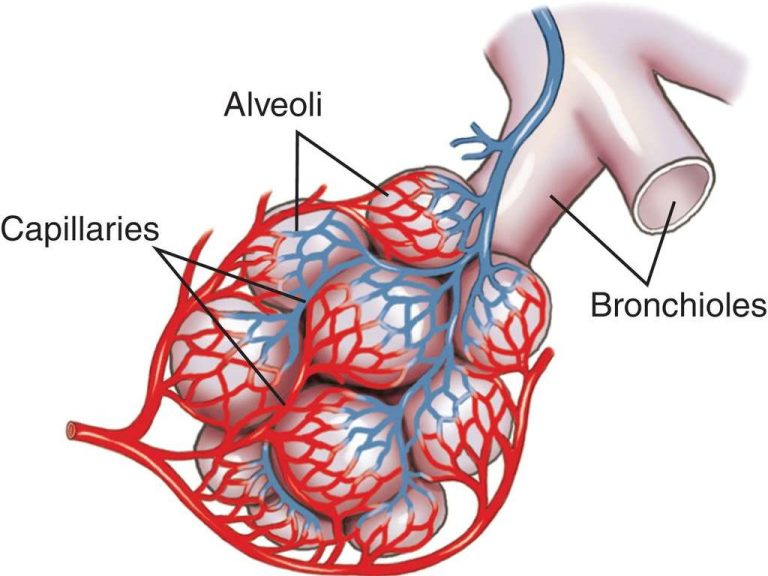

In our case we breathe: the chest expands and air is drawn into the windpipe (trachea) and then into the tubes (bronchi) that feed each lung. Our lungs are packed with smaller and smaller tubes (the bronchioles), some of them as thin as a hair, around 30,000 in each lung.

Each bronchiole ends with a small cluster of air sacks called alveoli. These are like bunches of tiny grapes or balloons, each covered with minute blood vessels (capillaries). It is here that the air finally meets the bloodstream, the oxygen atoms in the air pass through the fine walls (just one cell thick) of the capillaries to join up with iron atoms in the blood (in a special protein called haemoglobin – see HERE), to be carried around the body to wherever oxygen is needed. There are about 600 million alveoli in the lungs, and the surface area of each of these tiny bubbles adds up to a very large figure indeed – about the size of a tennis court!

The bloodstream has access to this huge area for two different reasons. As we breath IN, it absorbs vital oxygen (O2), but as we breath OUT, it gives up the waste product of carbon dioxide (CO2), which it has collected on its journey around the body, and which is passed back into the lungs to be expelled.

So we have:

IN halation: the bloodstream is enriched with oxygen.

EX halation: The blood gives up its waste CO2 to be expelled (to be reused by plants that returns oxygen to the atmosphere in the process known as photosynthesis).

So one circulation system doing two quite different but equally essential tasks.

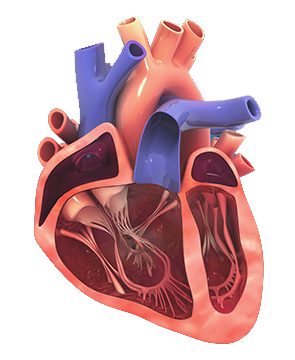

This system is driven by the heart, which powers both the enriched blood from the lungs to the rest of the body, and also the blood returning from its journey around the body to the lungs with its burden of CO2. (a biproduct of the body's use of oxygen). These two different blood flows have to be kept separate – so the heart has four chambers, two dealing with the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs, the other two handling the depleted blood returning to the lungs ; one pump, two different flows of fluid.

Rasi Bhadramani/ istock

This process is monitored and controlled by a special respiratory centre (medulla) in the brain stem. This, for example, monitors the level of CO2 in the bloodstream. CO2 increases the acidity of the blood; chemical sensors detect this and send a message to the brain which then increases the depth and speed of breathing, to expel more CO2, bring in more oxygen, and correct the acidity of the blood.

If the atmosphere contains too little oxygen (for example at high altitude), the body’s metabolism slows down to consume as little oxygen as possible, and blood flow to the limbs is redirected to the most critical organs, the brain and the heart.

Most of our bodies’ vital functions are carried out automatically and continue without our being aware of them. But breathing is different: we do have voluntary control over it. We can ‘take a breath’, ‘hold our breath’, stop breathing altogether. In theory we could end our own lives, but the brain has a failsafe mechanism which kicks in and forces us to breath. But the ability to control our breathing is vital – it enables us to swim, to talk, to sing, or to play a musical wind instrument like a flute or trumpet.

StockPlanets/ istock

The lungs have their own system of healthcare.

They produce a liquid called surfactant (an important component of modern detergents!) which helps to keep the alveoli open. The alveoli contain immune cells called bacteriophages which deal with infection. Mucus produced in the tubes helps clear pollutants and infected material.

If you have the inclination, the time and an active imagination, you maybe can sit down in your armchair and come up with a way that this respiratory system could have come about by chance over a very long period of time, by a succession of very small accidental changes.

But the result would be fiction, not science.

The evidence is entirely missing, and no two people would come up with the same result.

It would be like one of Rudyard Kipling’s ‘just-so’ stories, ‘How the elephant got its trunk’ (see right Kipling’s own illustration); the big difference is that Kipling never intended his stories to be taken seriously.

‘The life of the flesh is in the blood’ says the Bible (Leviticus 17.11), written three thousand years before William Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood. How can we close our eyes to this astounding demonstration of the Creator’s wisdom and intelligence?

"Let everything that has breath praise the Lord"

References: 1. 'Foresight' by Marcos Eberlin

2. 'Your Designed Body' by Steve Laufmann and Howard Glicksman

Psalm 150:6

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.