7

A long way to swallow

The giraffe story and why it’s important

15308757/ istock

It’s easy to admire the giraffe.

It’s the tallest land animal we know, a vegetarian that doesn’t kill or threaten other animals. We can hardly fail to be impressed by its extraordinary stature and anatomy and the unique and striking pattern of its hide, as it pursues its stately progress across the plains of Africa.

Sadly, the giraffe has become an emblem of something else. When we look at the giraffe, we are seeing evolution in action, so we have been told. Darwin did not mention the giraffe until a later edition of his book 'The origin of Species' (6th edition 1872), but his outline was clear. The giraffe started life as a much smaller short-necked animal. Some of them with a slightly longer neck found that they were able to reach the upper leaves of the trees not available to their fellows, which gave them an advantage, and over long periods of time they flourished, whilst those with shorter necks died out – 'survival of the fittest' in action. So eventually the giraffe became a unique species.

This story is simple enough, and so widely accepted and repeated that the giraffe has become an ‘icon’ of evolution, the standard ‘go-to’ example of Darwin’s process of evolution that we are told is responsible for all living things that we know today. "To biologists, the giraffe's long neck is a prime example of evolution's handiwork..." (Sofia Moutinho, science.org 17 Mar 2021) We look at the giraffe’s long neck, and we see evolution, ‘natural selection’, in action before our eyes.

or maybe not?

Stephen Jay Gould was a well-known exponent of evolution, one of the best known since Charles Darwin himself. This is what he wrote in his (American) Natural History magazine column in 1996:

"I made a survey of all major high-school textbooks in biology. Every single one - no exceptions ... use the same example to illustrate Darwinian superiority - the giraffe's neck. Giraffes, we are told, got long necks in order to browse the leaves at the tops of acacia trees ... available to no other mammal."

But Gould himself was not impressed, in fact quite the reverse. This was his comment:

" ... if we continue to illustrate our conviction (of Darwinian evolution) with an indefensible, unsupported, entirely speculative, and basically rather silly story, then we are clothing a thing of beauty in rags - and we should be ashamed... If we choose a weak and foolish speculation as a primary textbook illustration... then we are in for trouble…"

Here is one of the foremost evolutionists of our time speaking (Professor of paleontology and zoology at Harvard University etc.). He was an agnostic, not a religious devotee or creationist. But he says the story of the giraffe’s neck is 'indefensible’, ‘unsupported’, ‘entirely speculative’, ‘weak and foolish’, and 'basically rather silly’. He goes on to explain some of his reservations about the story:

"Even if we assume that the giraffe’s neck evolved as an adaptation for eating high leaves, how could natural selection build such a structure by gradual increments? After all, the long neck must be associated with modifications in nearly every part of the body (our emphasis) - long legs to accent-uate the effect and a variety of supporting structures (bones, muscles, and ligaments) to hold up the neck. How could natural selection simultaneously alter necks, legs, joints, muscles, and blood flows (think of the pressure needed to pump blood to the giraffe's brain)?"

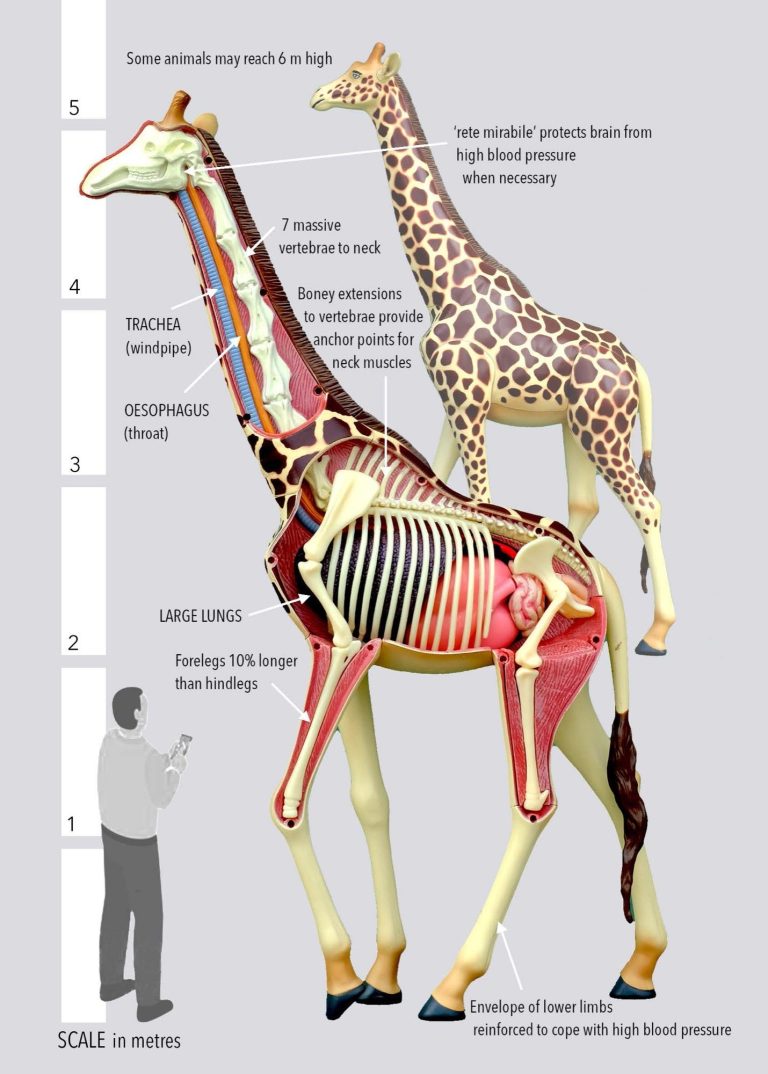

The giraffe’s extended neck (taking it up to maybe 6m in height) is backed up by a range of other special engineering features, without which the long neck would be a liability, not an asset. As Gould notes, they would all have to appear at the same time if the giraffe was to remain a viable organism.

Here are some of them:

1. Blood and oxygen supply

The brain demands a good supply of oxygen, but the giraffe’s brain is some 2.5m away from its heart and vertically above it for most of the time. A huge muscular heart (11.5kg or 25lb in weight) is vital and creates a very high blood pressure (2½ x that of a human and probably the highest in the animal kingdom) to make sure the brain’s demands are met. For such a large animal its heart rate is fast, about the same as ours, to keep up this pressure. But as with humans, high blood pressure can create problems, for example when the giraffe lowers its head to the ground to drink, a ‘rush of blood to the head’ could be fatal. So a web of small blood vessels (called the ‘rete mirabile’ or ‘marvellous net’) between the arteries and the brain reduces the blood pressure to acceptable limits when necessary.

The lower limbs could also be susceptible to damage, and recent research has found that giraffes minimise swelling in legs and ankles with the same trick that nurses use in dealing with high blood pressure: a tight wrapping of connective tissue around the legs act like an elastic support stocking. Thick-walled arteries around the knees restrict the flow of blood, and the entire vascular system, the kidneys and the heart, are all designed to function at this exceptionally high blood pressure.

2. Windpipe (trachea) and lungs

The giraffe’s windpipe is a tube around 2.3m long from mouth to lungs, and 35–51mm in diameter. This means that there is a large volume of air in the trachea itself before it gets to the lungs This air has to be completely expelled at every breath, otherwise at the next breath the giraffe will draw in again some air which has already been used and will soon suffer from oxygen starvation and/or carbon dioxide poisoning. So, the giraffe’s lungs are huge. Its rate of breathing is also slowed down to prevent ‘windburn’ in the trachea, the effect of large volumes of air constantly whistling at high speed backwards and forwards through the long windpipe.

3. Throat (oesophagus)

The giraffe is a ruminant, i.e., having once swallowed its food, it later regurgitates it for further chewing and digestion, before swallowing it again. The swallowing action, like our own, is a complex action that relies on a progressive squeezing of the muscles around the throat, programmed by impulses from the brainstem. Due to the long neck, the giraffe’s oesophagus is similar in length to the trachea, around 2.3m. So, you can imagine the muscles and programming required to both swallow and then regurgitate food over this distance. Of course, any change in the length of the neck would require the swallowing action to be reprogrammed.

4. Long legs

Can you imagine a giraffe with short legs? It’s astonishing that the story of the giraffe focusses entirely on the length of its neck and ignores the extraordinary length of its legs. Clearly the effectiveness of the neck extension would be much smaller if the legs had stayed the same length as its supposed ancestor. Interestingly, the front legs are 10% longer than the back legs, so shifting its centre of gravity backward and giving the animal its distinctive continuous sloping backline and easy motion.

5. The evidence

There are just two animals classified as being in the ‘giraffa’ family, the okapi (see picture) and four species of the giraffe itself. The okapi is a much smaller animal similar to a zebra. Evolutionists tell us that both descended from an unknown common ancestor. So where are the fossils of the multitude of intermediate forms which must have existed over eleven million years (so we are told) as the giraffe evolved and its neck grew longer and longer?

There is no evidence that the ability to reach the highest leaves of the acacia tree is crucial to the giraffe’s survival, or ever has been. Scientists now wonder whether other factors are involved, e.g., the giraffe’s use of its neck as a weapon in fighting its competitors – the one with the longest, strongest neck wins the mate, and their offspring carry the same advantage.

Recent research has now defined some 97% of the giraffe’s ‘genome’, the complete blueprint of the animal held in coded form in its DNA. Comparing it with other similar animals like the okapi, the research identifies around 490 genes (smaller packets of information within DNA) unique to the giraffe, genes which define the outstanding and unique features of its cardiovascular system, bone growth and so on. The current theory of evolution has only one available explanation for these unique genes: they are the result of accidental changes and errors in DNA over long periods of time, The chances of this happening are beyond credibility. ‘Silly’ is the word that comes to mind.

Why is it that ‘scientists’ generally hold such a position of influence and respect in our society? Because we believe they deal in facts, they can back up their theories with hard evidence. Sadly, that is often far from being the case. There is as much evidence for the story of how the giraffe got its neck, as there is for Rudyard Kipling’s stories of how the elephant got its trunk (see HERE) or the leopard its spots! That is why a distinguished scientist calls it ‘weak and foolish’, and ‘basically rather silly’.

The real story stares us in the face but is deeply unacceptable in the atheistic materialist world we have built for ourselves. This story is exhibited, not just by the giraffe, but by every living thing that we care to examine; an astounding display of purposeful design, intelligent engineering and programming, that we recognise from our own experience, if we only open our minds to it.

The giraffe, and other unnumbered miracles of creation, are God’s handiwork. He invites us to recognise and worship Him as our Creator, and to seize the hope that He offers us through His Son Jesus Christ.

Many in our world dismiss this hope as childish and ‘silly’. The giraffe tells a different story.

Like children, we should listen.

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.