5

Your junk appendix

For generations we have been conditioned to believe that the appendix is completely useless, a piece of sometimes troublesome junk left behind by the process of evolution; just one of many organs which may have been useful to our ancestors at some stage but have since been abandoned.

Today we know better.

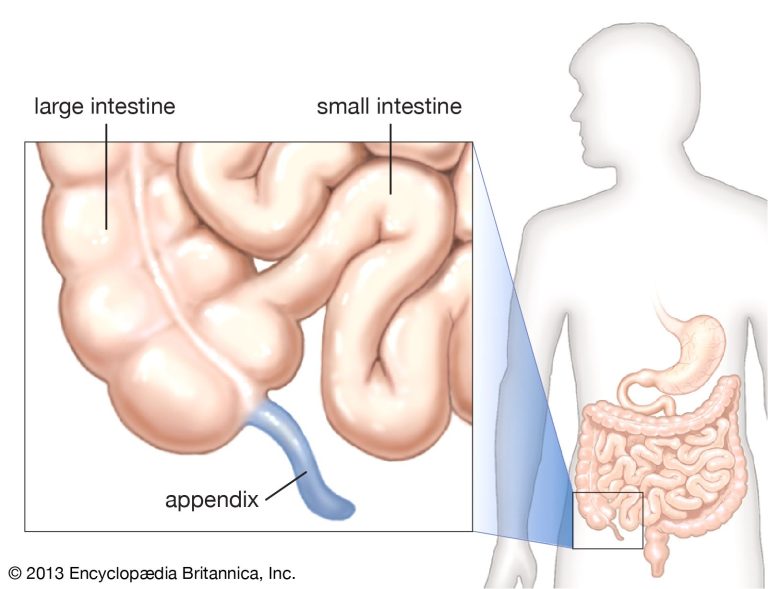

The appendix is attached to the digestive tract, a small cul-de-sac in a position where it can act as a reservoir for the good bacteria which are essential to digestion (see picture). Flushing out the system leaves the appendix untouched, and the bacteria it looks after can then be used to quickly repopulate the gut and restore the normal process of digestion.

It is also rich in lymphatic tissue, which is fundamental to the immune system, and may be particularly active during the early years of development. It is most certainly not junk.

Darwin himself described these supposed relics of evolution as ‘residual’ organs, but they became better known as ‘vestigial’ organs; vestiges supposedly left behind after their function had long ceased.

In 1895 Robert Wiedersheim listed over 100 vestigial organs. One of his followers, Horatio Newman, upped the number to 180, ‘sufficient to make a man a veritable walking museum of antiquities’, he said!

Science moves on. Research in 2012 and 2017 has shown that the appendix is not vestigial at all. It is obvious that ‘vestigial organs’ say nothing about evolution, but are simply a measure of our ignorance. The more we know, the shorter the list becomes. Today the list is down to a handful of oddities like wisdom teeth, male nipples, and body hair – not a great return on several billion years of evolution!

"So the Darwinian argument that the appendix is a vestigial organ that supports evolutionary theory is itself vestigial, a leftover of nineteenth century Darwinian biology. We know better now." Marcos Eberlin, ‘Foresight’

Rasi Bhadramani/ istock

DNA under the microscope

More junk! This time it's DNA

With the explosion of research on DNA at the end of the twentieth century, along came some more ‘junk’!

As scientists explored the huge new field of genetics, opened up by the discovery of DNA, something rather strange became evident – it appeared that a large part of DNA was inactive. The genetic code was there, but it didn’t seem to be doing anything; a large part of the genome (the entire body of genetic information) was not coding for anything.

The answer from the evolutionists was not slow in coming. This was more junk – ‘JUNK DNA!' Billions of years of evolution, and its myriad failed experiments, had left behind a lot of meaningless debris in every cell of our body.

‘It is a remarkable fact that the greater part (95% in the case of humans) of the genome might as well not be there, for all the difference it makes.’

Richard Dawkins, ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’ 2009

In 2012 came the results of the ENCODE project. Four hundred and fifty scientists across the world, working together to map the whole of the human genome for the first time, released thirty major papers simultaneously.

In 'Nature' magazine they noted that they were able to "assign biochemical functions for 80% of the genome… It’s likely that 80% will go to 100%. We don’t really have any large chunks of redundant DNA. This metaphor of junk is not that useful".

Delicately put!

What that really means is that the idea of ‘junk DNA’ is itself junk.

The New York Times announced:

"The human genome is packed with at least four million gene switches that reside in bits of DNA that once were dismissed as ‘junk’ but that turn out to play critical roles in controlling how cells, organs and tissues behave". You do not need to know what a ‘gene switch’ is to get the message: bits of DNA previously thought to be junk turn out to be critical for life.

Take one particular organ as an example, not the appendix this time but the liver. The liver’s function is well known in processing food and dealing with waste products. In 2013 it was found that the liver was controlled by one of these stretches of DNA that had previously been dismissed as junk; a series of 3,000 genetic switches outside the gene for the liver (‘epigenetic’, meaning ‘outside the gene’, is the word used) but crucial to the gene’s function.

yodiyim/ istock

The human liver

Today the Encode project continues, now on ENCODE 4.

It is now obvious that the concept of the ‘gene’ as the only or main active component of DNA is a huge oversimplification, and the dismissal of other regions of DNA as rubbish is based on ignorance. If you think that sounds just like the argument for vestigial organs, I think you are right; so-called ‘junk DNA’ is just a measure of our ignorance about how DNA really works. If two supposed pillars of evolution, vestigial organs and junk DNA, have both been discredited, what does that say about evolution?

As we journey through life in the twenty-first century, we are assaulted by information, battered by a myriad of all kinds of influences. If we are not very careful, we can find our lives ruled by junk, by the superficial, the sensational, by ignorance and prejudice and misinformation of all kinds.

I have been reading the Bible ever since I was a teenager.

It is not junk. It is sometimes difficult to understand, but it is never junk. If it ever appears junk, as some people claim, it is just a measure of our ignorance, and we need to concentrate and educate ourselves in God’s way and reject the pressures to conform to the God-denying spirit of our age, which wrongly claims to be based on science.

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.