14

The perfect copy

British Museum

For thousands of years, the only way of copying something was to use exactly the same technology as produced the original, but simply repeat it, if necessary over and over again. When the great rulers of the ancient world wanted multiple copies of a royal decree to send out to their provinces, they set to work an army of scribes, each with their own clay tablet, pressing the same letters into the soft clay.

The Jewish scribes and the medieval monks spent months, even years producing a single hand-written copy of a sacred text. The invention of printing brought a way of making multiple copies, but it was an elaborate and expensive process quite unsuited to most everyday documents.

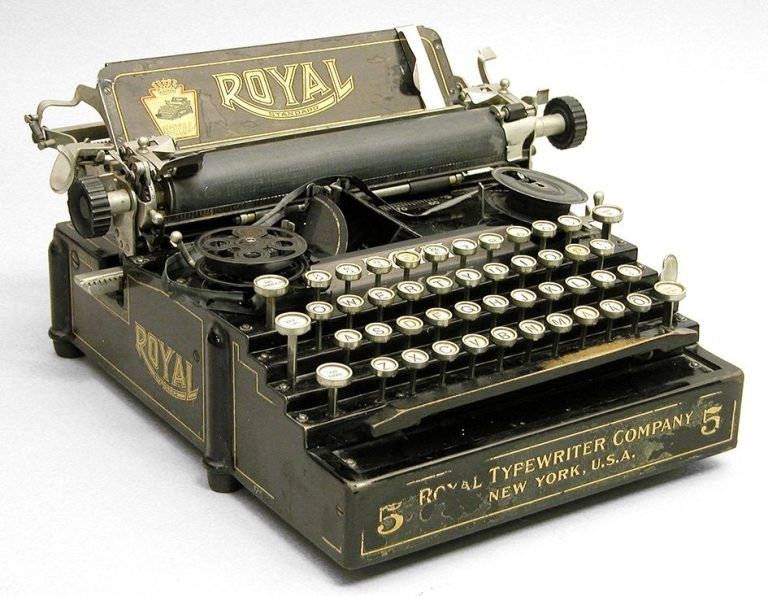

The typewriter (patented 1878) was a revolutionary step towards enabling multiple copies of ordinary documents. The impact of the type was strong enough to penetrate several layers of very thin paper, and with the insertion of thin sheets of carbon paper between the layers, several copies could be produced at the same time – hence the term 'carbon copy’ still used today. The word ‘facsimile’, meaning an exact copy, gave its name to the Fax machine, now about as obsolete as the typewriter.

Photography, first on glass plates, then film, then digital sensors, was another massive step forward. Today the ink jet printing technology developed for documents and pictures has been adapted for 3D printing, so that small components can now be copied and reproduced exactly in three dimensions.

3D Printer prints a model of the Eiffel Tower

It surely comes as no surprise to us to find that the natural world, including our own bodies, uses very sophisticated copying techniques that make our human technology seem quite rudimentary. These techniques, we are told, came about by chance.

"The point, which science has long understood, is that bits and pieces of... complex machines may have different – but still useful – functions... Evolution produces complex biochemical machines by copying, modifying and combining proteins previously used for other functions..."– so says biologist Ken Miller. He is trying to explain how an amazing molecular machine like the tail of the bacteria (‘flagellum’) and its motor (see HERE) could arise by chance from something simpler. He apparently considers processes like "copying, modifying and combining" to be quite simple mindless procedures that can easily happen by chance without any vision or foresight.

Human experience tells us the very opposite.

Take the car for example.

AFTER 80 YEARS, THE LAST OF THE VW BEETLES

Today’s pre-electric models are often the result of continuous development (‘evolution’?) over a period of many years. The first Volkswagen (‘people’s car’) was designed by Ferdinand Porsche in 1938, and came to be known as the ‘Beetle’ from its distinctive shape. The character (sometimes called its DNA!) of that original car is still clearly visible in the car which finally ceased manufacture in 2019. The latest version was the result of a long process of intelligent copying, creation, selection and refinement over 80 years or more. There was nothing easy or aimless or mindless about it. The whole process would be impossible without the creative vision of the engineers who managed it. In my own experience the transformation and upgrading of an existing building to a new use can be even more demanding than designing a new building from scratch.

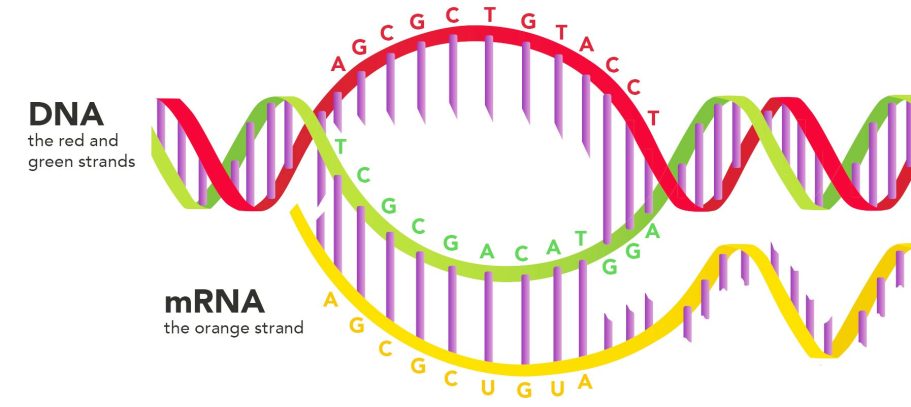

Our own existence depends on a copying process of extraordinary complexity and miniaturisation. The data that describes many of our characteristics as individuals is carried by a four letter code (ATCG – see the graphic below) in the DNA molecules in every cell of our bodies. The ‘letters’ are in fact four different chemicals called ‘bases’. But all this information is securely stored in the core – the ‘nucleus’ – of the cell and never leaves it. How can it be used?

It has to be copied.

DNA is like a reference library where you are not allowed to borrow the books. You have first to visit the library, find the book you need, copy the information you need by writing notes or making photocopies, and then leave the library, taking your notes with you to be used somewhere else. The books remain, safe and intact ready to be referred to again and again. But some of the information in them has been freed for use outside the library.

William Barton/ shutterstock

In the DNA ‘library’, this process involves another remarkable molecule called RNA, which appears to be purpose-made for the job. First it enters the library (the core of the cell) to find the piece of DNA code it needs (not that easy – the human genome has a total of over three billion letters of code).

THE BRITISH LIBRARY

The four 'letters' of the DNA Code:

A for Adenine A always pairs with T

G for Guanine C always pairs with G

C for Cytosine

T for Thymine

If you know one strand of DNA, you can

work out the other one.

RNA makes a copy of DNA

DNA is made up of two strands coiled together in a double spiral (see red and green strands in the graphic above – the purple links are the ‘bases’ which make up the code, two ‘letters’ to each link). When it is being copied, a stretch of DNA unzips into two separate strands to create a template for the single strand of RNA (orange) to follow.

RNA creates a strand that matches the DNA code and then leaves, carrying with it an exact copy of the information it needs. This is then delivered to the various machines in the cell (ribosomes) which make the proteins on which life depends. Hence the term ‘messenger’ sometimes applied to RNA. The DNA zips itself back together ready to be used again – the ‘reference library’ is intact. It will be copied in this way a myriad times every second of our lives.

This is of course a huge over-simplification of the amazing chemistry involved, but maybe it’s as much as most of us non-specialists need to know.

Big Question: how accurate are these copies on which we depend? DNA has its own repair and self-correcting mechanisms, resulting in an estimated error rate of around one in a billion. Not bad for a process that they say happened by accident!

This copying process did NOT evolve.

Evolution can only start with life – the ‘survival of the fittest’ only applies to living organisms. The DNA code and the ability to copy it are essential before life can even begin. So if they did not evolve, where did they come from?

No answer. Science is silent.

Science is silent on a lot of things, especially on the big, really important questions. For authoritative answers we have to go elsewhere. God’s Word tells us that the key to meaningful life now and a wonderfully fulfilled life in the future also involves copying – copying a model that God has given us. Not the celebrities, the bloggers and ‘influencers’ of our society, but His son and our saviour Jesus Christ:

"Copy me, my brothers, as I copy Christ himself"

the Apostle Paul 1 Corinthians 11: 1, Phillips Translation

That’s not easy. But copying never is.

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.