3

The pride of the peacock

Let-c / istock

“The sight of the peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick.”

(Charles Darwin, private letter to his friend Asa Gray, 3 April 1860)

That seems rather a strange reaction, doesn’t it?

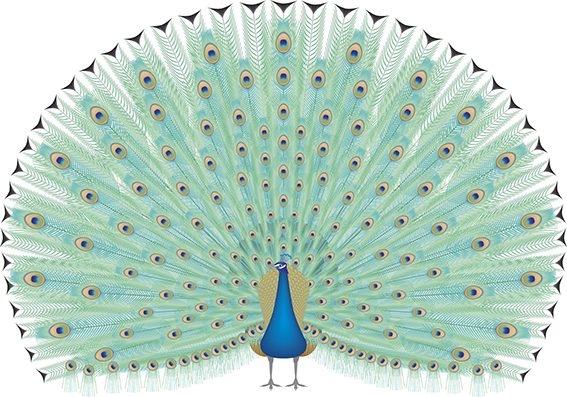

Maybe you have never seen a peacock with its tail feathers fully displayed as part of its courtship ritual. If so see here later. Does it make you feel sick?

Darwin had a problem. He realised that the peacock’s display posed a real problem for his theory of evolution, which demanded that every change, every advance up the ladder of evolution depended on its practical usefulness, its survival value. Yet here was a highly decorative feature which seemed to be of no practical value but rather made the peacock more conspicuous and slowed it down so that it was more vulnerable to predators and less likely to survive.

Some years later Darwin came up with an explanation. The peacock’s display he said was an example of ‘sexual selection’; it was demanded by the female in her selection of a suitable mate, and the genes of the most colourful and beautiful bird would be perpetuated in their offspring. Generations of evolutionists have adopted this idea when confronted by examples of design and beauty which are otherwise inexplicable, but they have not always found it very convincing.

Let’s forget about that for a moment, and just look at this wonderful exhibition in more detail.

What makes the peacock’s tail so special?

alphabetMN/ istock

Symmetry

When fully displayed the feathers form a complete semicircle of 180◦ or rather more, with the stems of every feather pointing directly towards the geometrical centre of the semicircle, even though in fact each feather is growing independently from its own follicle over quite a wide area of the peacock’s back. So this seems to be an exercise in pure visual symmetry without any practical purpose.

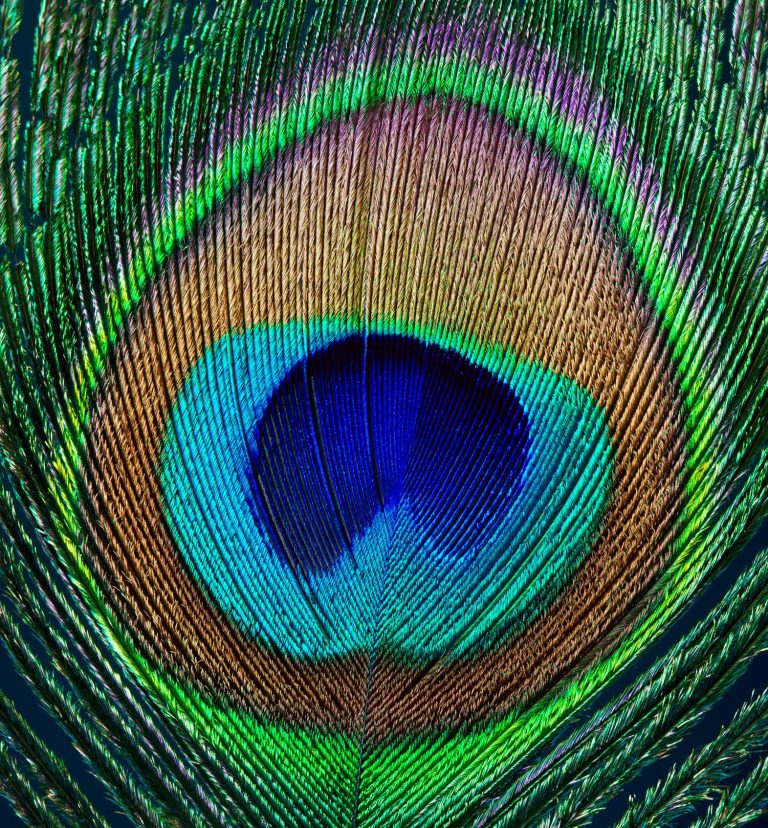

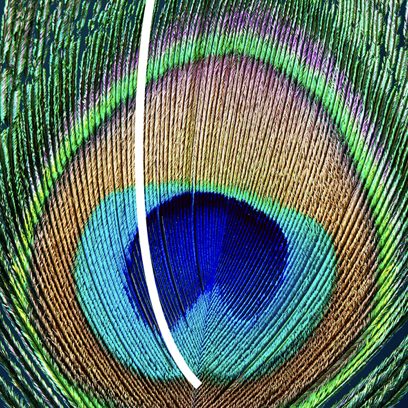

Each feather has a main stem (white) with ‘barbs’ (brown) branching off the stem. The barbs are then covered with ‘barbules’, tiny ribbon-like threads, and this is where the colour comes from. There are about 200 feathers in all, of two types, the ‘eye’ feathers (170) and the ‘T’ feathers (30). Each ‘eye’ feather ends in a spectacular iridescent multi-coloured design usually called the ‘eye’, whilst the darker and longer ‘T’ feathers form a backdrop and an elegant fringed border to the edge of the semi-circular display.

The Eye feathers

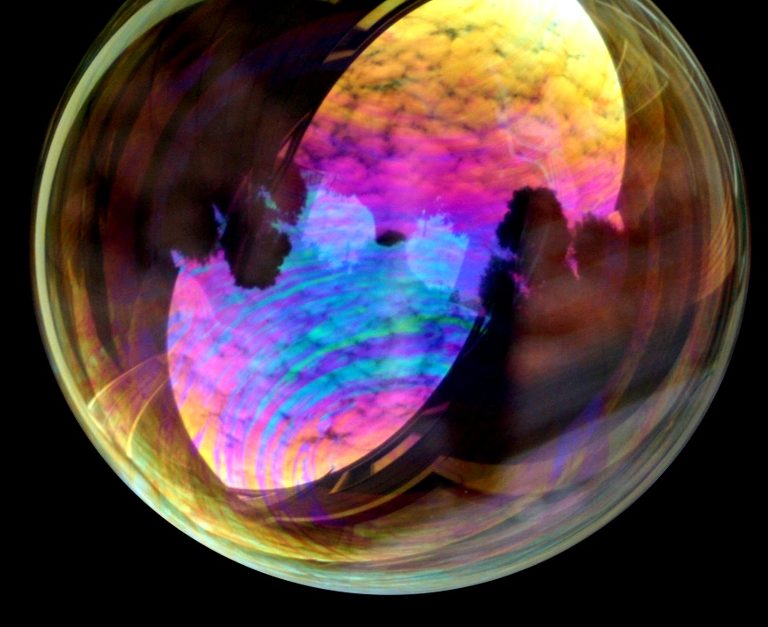

The colours of the ‘eye’ are iridescent – in other words the colour changes according to your angle of view. This is because the colour is not the result of pigment but rather the structure of the barbules and the way they interfere with white light in an optical effect known as ‘thin film interference.’ Think for example of a film of oil or petrol floating on a puddle of water, which produces a kaleidoscope of colours, or the surface of a soap bubble (see pictures).

This iridescence is found in a variety of animals: butterflies, insects and birds like the humming bird and the kingfisher, and it depends in every case on an incredibly fine and precise structure. As far back as 1704 Isaac Newton commented in his famous book ‘Optics’ that the iridescence in peacock feathers was due to the fact that the transparent layers in the feather were so thin.

How does this ‘thin film interference’ work on the peacock’s feather? The ‘barbules’ of the feathers are coated with three thin layers of a transparent protein called keratin. By thin I mean really thin – about 0.4 – 0.5𝜇 where 𝜇 is a micron, one thousandth of a millimeter, very close to the wavelength of light itself. White light is reflected, retarded (slowed down) and scattered inside these films and emerges as a colour; which particular colour depends on the thickness of the film and other factors.

So the colours of the eye in the peacocks feather depend on very fine control of these keratin coatings at a microscopic scale. There are basically 5 different colours in the ‘eye’, and each requires a different thickness of film. Where a barb extends right across the eye design the barbules need to change colour several times (see diagram). There are a total of about 100.000 barbules in each eye pattern and they all need to change colour at a precise position on the barb in order to maintain the overall design of the eye and the boundaries between the different colours. And to build up the eye one strand at a time, each barb and its barbules is different. All this has to be programmed into the feather as it grows from the follicle.

ithinksky/ istock

A writer on this subject makes this comment:

‘The theory of thin films as the cause of iridescence… cannot but inspire one to marvel at the perfection of nature’s method of producing these colours with such uniformity throughout successive generations, especially when a slight variation in thickness of the films of the feathers of a bird, such as a peacock, would be enough to alter its colouring completely’ (C.W. Mason – ‘Structural colours in feathers II.’)

Who or what is this mysterious force he describes as ‘nature’ ?

Remember this – these feathers are shed every year and completely regrown, recreating the same exquisitely fine tolerances time after time, for generation after generation. This is only possible because every detail of the peacocks tail is stored as genetic information in the peacock’s DNA. As you can imagine, a lot of information is required. One writer suggests a minimum of 20 separate genes, many thousands of units of chemical information that according to evolution are merely the sum of various mistakes and copying errors over the generations, without intelligence, control or design.

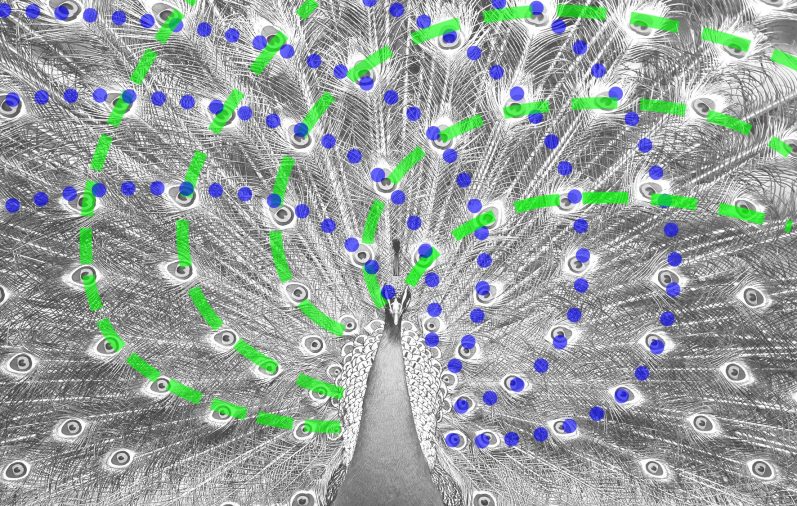

Distribution of the eyes

The eyes at first glance appear to be randomly distributed across the face of the display – but look a little closer. You will see that the eyes are arranged in arcs or spirals, starting close to the body of the bird, and then flattening out towards the edge of the display. This is especially obvious when the tail is only partly open (lower picture). This is a type of curve (logarythmic) very widely found in nature, in plants and sea shells – see for example the curves of the florets on the head of a sunflower (see picture below).

eROMAZe/ istock

Wirestock/ istock

Remember, each eye marks the end of an eye feather. These curves are only created because each successive eye feather is exactly the right length to place the eye in its correct position on the curve. In other words, each feather, whilst appearing to be growing independently from its own follicle, is in fact linked to all the others by a ‘programme’ that ensures each feather grows to exactly the right length and then stops, so that the eye occupies its right place on the curve and in the overall display.

Does this sound like an accident to you? A ‘programme’? Have you ever heard of a programme created by accident? Ask a computer programmer whether what he does could happen by accident, and you will get a rather dusty answer! Then ask him if a few small random changes in his code would improve it, and you will get a similar response – but that is what evolution demands.

Darwin’s idea of ‘sexual selection’ was not his finest hour. There are numerous objections to the idea, and some biologists will admit to them, but this is not the place to deal with them. The theory of evolution is pathetically inadequate to explain the splendour of the peacock’s tail and the astonishing precision bio-engineering and programming which make it possible. Here is the work of a supreme creative intelligence with the wisdom to include such abundant beauty in his creation, for our pleasure and to display his glory.

With acknowledgements to Prof Stuart Burgess, author of ‘Hallmarks of Design’ –

Day One Publications.

Here comes bucorus bicornis, the greater hornbill – another headache for Darwin!

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.