1

The accidental gearwheel

Writing in 1802, an English clergyman called William Paley imagines himself as a traveller crossing a heath. He stumbles across a pocket watch lying amongst the stones at his feet. He realises how different the watch is from the stones – he can tell from the way it is made, its organisation and its obvious purpose that the watch had a designer and maker.

He sees a link between the watch and the natural world and suggests that many features of nature, particularly of the human body, show similar evidence of a designer. So in his book 'Natural Theology' Paley spells out the classic argument for Design in Nature, an argument that has been debated ever since. Nature itself, he says, presents its own evidence for a supreme designer and creator.

When Paley opened the back of his pocket watch he would have seen a complex arrangement of gearwheels large and small, all working together to turn the hands of the watch at precisely the speed required.

Whilst he saw similarities between the watch and complex organs like the eye and the ear, he would surely never have believed that nature might contain its own version of the gearwheel! Yet that is what has now been discovered (published in 'Science' magazine Sept 2013).

This is 'issus coleoptratus', a small insect 5–6mm long ,

common throughout Europe. It doesn't fly, but it is a planthopper, one of the world's great jumpers, accelerating at nearly 400 gs (acceleration due to gravity) as it takes off, propelled by its two strong back legs.

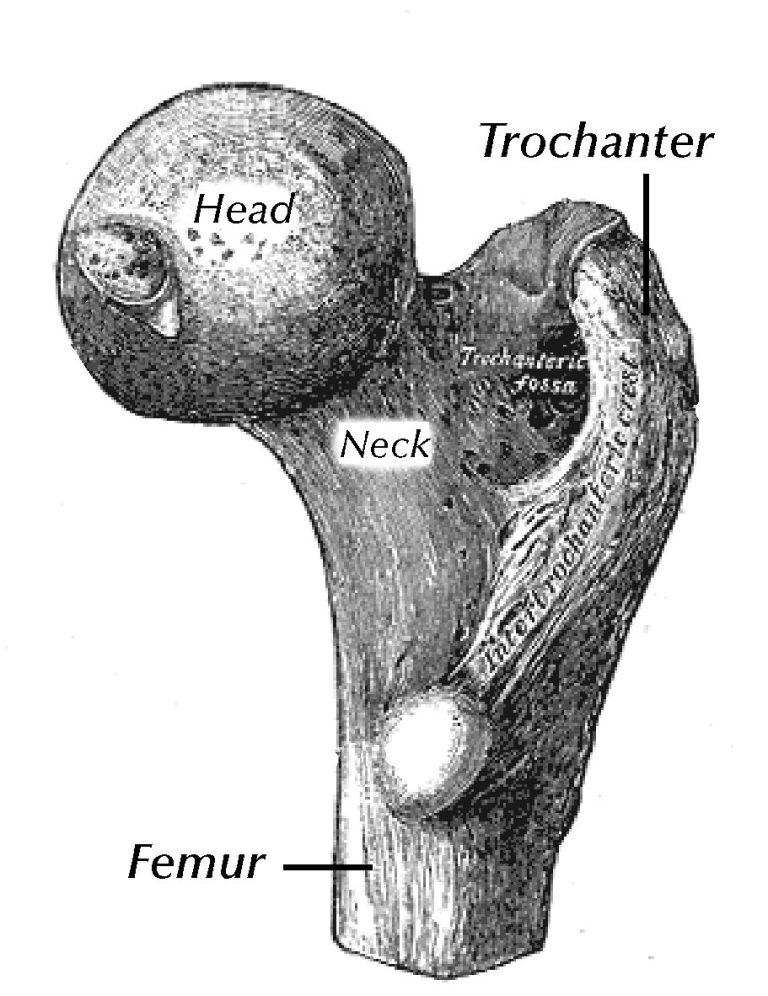

It may be helpful to compare the insect's leg with the more familiar human leg (see right). The human femur has a large bony protrusion at the top, just below the ball head that fits into the socket of the hip. This protrusion is called the 'trochanter' (in humans there is a 'greater' and a 'lesser' trochanter) and it acts as a main attachment point for muscles at the top of the thighs.

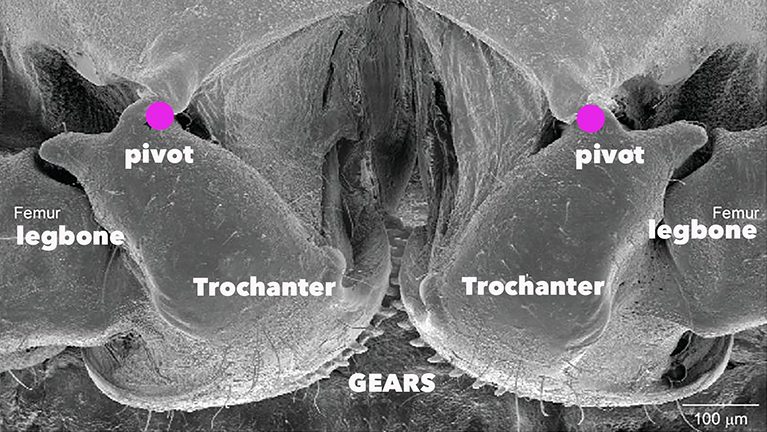

The insect has a similar arrangement, but part of the trochanter widens out into a flat disc. These two discs (one for the right leg and the other for the left) are large enough to touch each other. Where they touch they interlock with a series of small teeth or cogs around the edge of the disc (see scanning electron micrograph below). This means that the two back legs can be locked together to move simultaneously but in opposite directions.

Malcolm Burrows and Gregory Sutton

This arrangement makes sure that when 'issus' takes a huge leap, both legs 'trigger' at exactly the same time, otherwise the unfortunate bug might spin uncontrollably in the air. Each leg has its own set of muscles, but the small signals that trigger the jump are not precise enough to ensure absolutely simultaneous motion at very high speed – hence the 'gears' to synchronise the movement of the two legs.

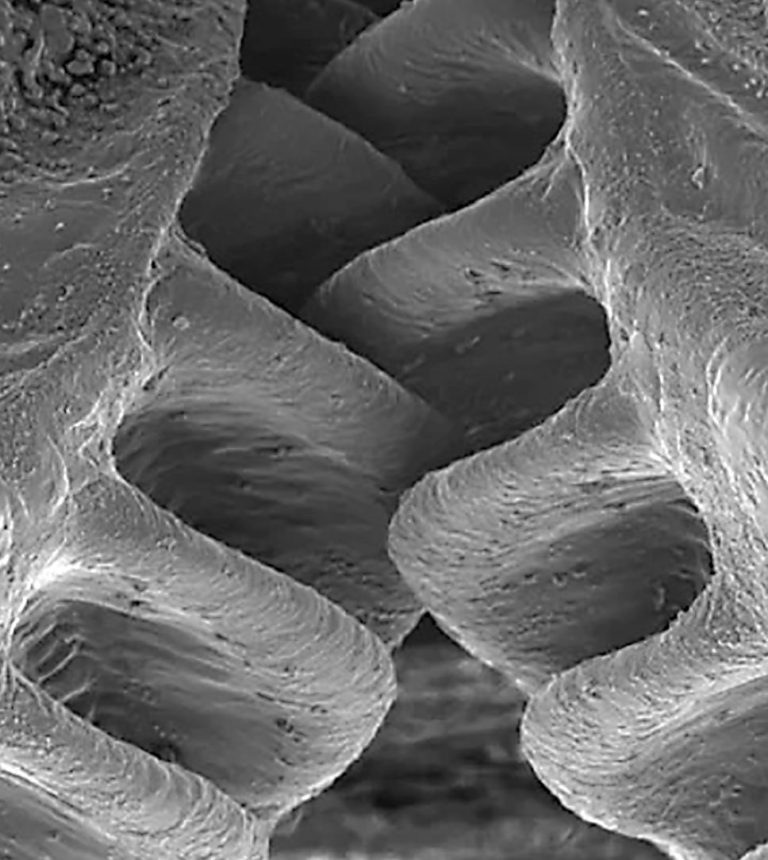

The cogs or 'teeth' are rather different in shape to the human-engineered version. They have a more wave-like or 'shark fin' profile, and are special in two ways:

• They are very, very small (see the dimension in microns – a micron is 1/1000 mm).

• They operate at an incredibly high speed – a short burst at almost 50,000 teeth per second.

By any definition this arrangement is a 'machine' – separate but interrelated components working together to achieve a particular objective, in this case synchronous movement. Did this machine have a designer, or did it originate from an unguided process of evolution?

Can evolution produce machines?

In 1949 J.B.S. Haldane, a well known British evolutionist, claimed that evolution could never produce 'various mechanisms, such as the wheel and the magnet, which would be useless till fairly perfect'. Leaving aside what he meant by 'fairly perfect'(!), presumably he felt on safe ground, as at the time no such 'mechanisms' were known to exist in nature. Darwin himself made a similar comment (see BELOW)

"If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possible have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down"

Charles Darwin 'Origin of Species' 1859

As science has probed deeper, the picture has changed.

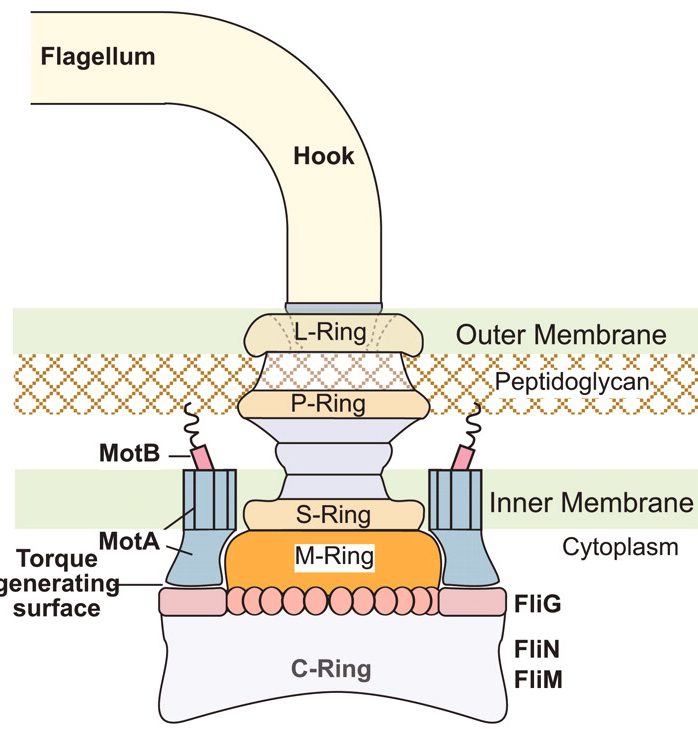

Nature does have machines, many of them. One of the best known is the motor that drives the flagellum (the whip-like tail/propeller) of a bacteria, a fast spinning rotor that contains all the finely tuned components that we would expect from an engineer (see right). As for the magnets referred to by Haldane, a number of examples are now known of animals that use magnetic sensors to navigate, including turtles, monarch butterflies and bacteria.

Jasmine A Nirody et al – ResearchGate

The astonishing rotary motor that drives the tail (flagellum) of a bacterium. It has all the components that we would expect from an electric motor of this type.

Haldane recognised the enormous problems of explaining how such precise mechanisms including a number of separate components all working together, could originate from an unintelligent evolutionary process – and in 1949 he knew nothing about the information requirements of such systems.

The subminiature gearwheels in this tiny planthopper illustrate the problems involved. You need two separate components (the trochanter), identical except that one is right-handed and the other left. The shape and strength of the teeth need to be sufficient to transfer the necessary energy but with minimal friction; the two sets of teeth need to be perfectly formed and spaced to mesh together without jamming up; the ‘pivot’ of each wheel needs to be accurately placed to achieve rotation without eccentricity; and so on.

Can you imagine the problems of constructing such a machine by trial and error, using only the random changes ('mutations' – see DESIGN) provided by the evolutionary process, and with no blueprint, no conception of what the actual role of this mechanism is? And each small step towards the finished machine needs to work well enough to confer some significant advantage on that particular insect, so that it can be perpetuated on the 'survival of the fittest' principle? Otherwise it will simply be lost.

These cogwheels have not been carefully machined from inert material like brass or steel or nylon. They are built from living cells, able to grow, repair and rebuild themselves. Every time that 'issus' moults, it sheds and rebuilds this mechanism. How does it know how to do that?

This is where we have a big advantage over Charles Darwin. We now know that every cell of issus' body contains the required blueprint in the code of its DNA, and each cell has the tools needed to read and interpret that code and build on its instructions. Note too that issus has a built in body clock that tells it when to shed and rebuild this vital mechanism. Like any engineering structure it requires regular maintenance/replacement.

Precision dimensional rquirements for interlocking cogs. Other criteria for an engineered mechanism:

1. construction material – is it strong

enough for anticipated loading, will

it withstand constant use etc.?

2. lubrication requirement

3. maintenance schedule

4. Replacement schedule

5. permissable 'downtime' for

replacement

It is not rational to believe that this mechanism happened by accident, without plan, without purpose, without intelligence. We are entirely justified in asking who engineered the gear-wheel.

If you can believe in accidental gearwheels, you can believe in anything: Santa Claus, the tooth fairy, flying pigs, the whole gamut of superstitions that atheists like to bandy about, nothing is beyond your reach.

Accidental gearwheels? Not a chance!

So how about an accidental brain? See next in GALLERY

Injenerker/Dreamstime.com

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.