12

Ladybird, ladybird . . .

ConstantinCornell/istock

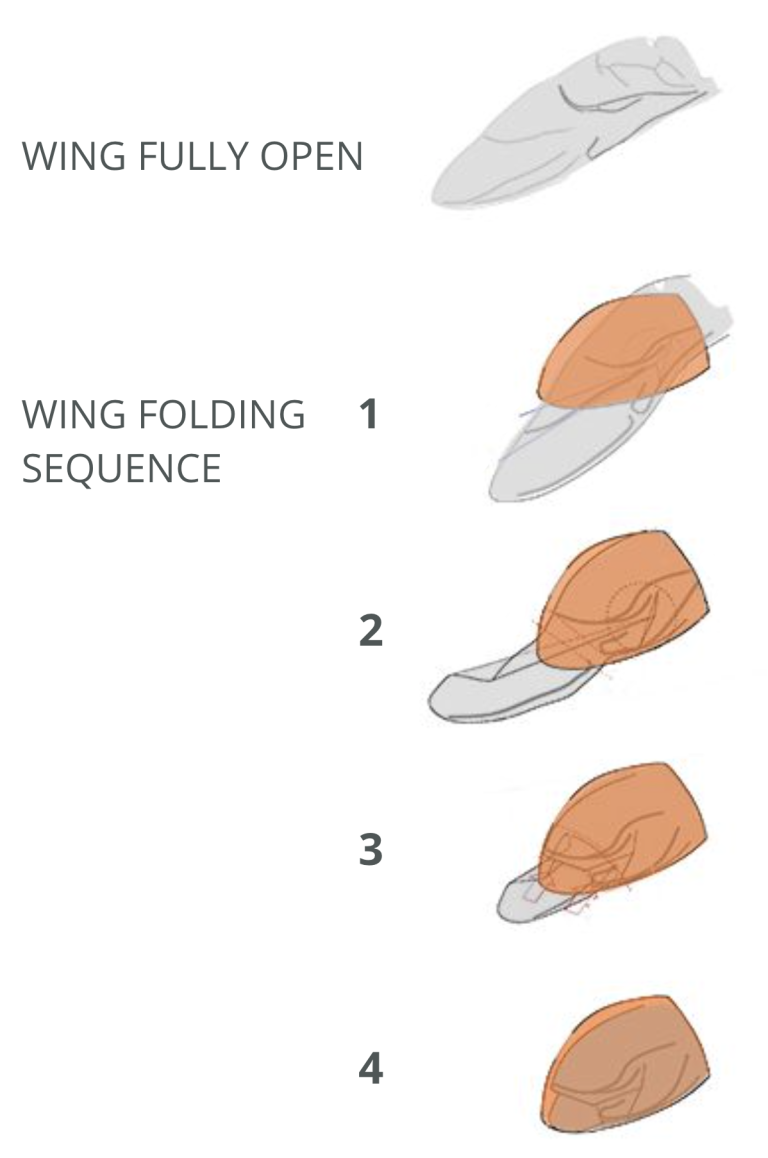

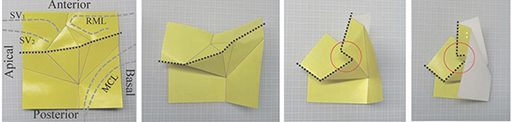

In 2017 some Japanese scientists decided to investigate how the ladybird managed to fold up its long wings to fit under its small red wing-cases. Part of one wing case (proper name 'elytron') was cut away and replaced by an artificial elytron made of clear resin, so that they could see what was happening inside. Then using advanced high speed photography they filmed the tiny bug as it opened and closed its wings, something it does a thousand times or more during its brief lifespan.

What they found (for full report see HERE) was a complex pattern of folding which they compared with ‘origami’.

'Origami’ is the Japanese art of paper-folding which is popular in many parts of the world. A single small sheet of paper is folded a number of times in different ways to form any number of different 3-dimensional objects, from a boat to a swan to a jumping frog etc. The comparison of the ladybird’s wing with the simple paper engineering of origami is interesting, but also throws into relief the amazing advanced engineering of the ladybird. For example:

1. A sheet of paper has fixed qualities of strength and stiffness. Once it has been folded the page is permanently creased and deformed. The ladybird’s wing is quite different, because it can change its properties – the main supporting veins of the wing can be soft and flexible for folding and stiff and strong for flight. Where a human engineer would need to build a fixed combination of rigid rods and flexible hinges, the ladybird’s wing can change its properties to suit its function.

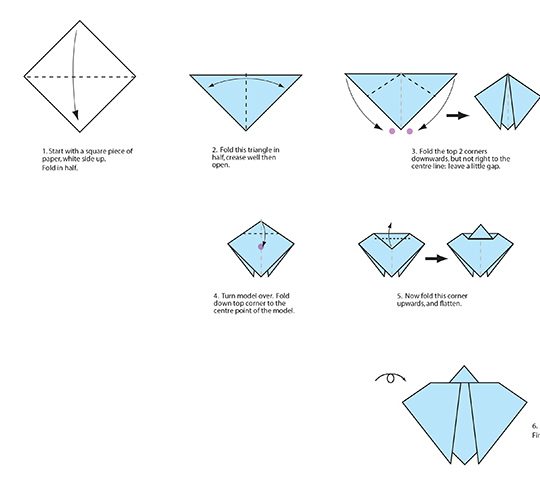

2. The origami model requires the folder to decide from the beginning what he/she is trying to create, and then carry out a strict sequence of folds in a particular order to achieve the end result.

The very first fold is made knowing what the eventual target is to be.

A very simple origami pattern

for a paper ladybird.

If the ladybird evolved, as so many people believe, then there is no target. Evolution cannot envisage any targets or choose any particular destination. It does not know that this wing needs folding or why – any folding is purely accidental, the result of the random changes (‘mutations’) on which evolution depends. If a fold happens to take place, and if it also proves an advantage of some kind, then it may be kept, until such time as the next ‘useful’ fold happens to come along. The overwhelming majority of accidental folds will be harmful or fatal: the chances of two or three useable folds coming along together are astronomically improbable. The wing-case had to evolve at the same time, because a folded but unprotected wing is exposed to more serious damage – any impact could damage several layers at once.

The wing is both much longer and also wider than its case, so a pattern of both long-wise and width-wise folds is needed, with a particularly complex pattern under the centre of the wing (see circled area in illustration above). Again information is the key – the amount of data required to specify the direction, length and precise position of each fold far exceeds the capacity of any single mutation.

The wing case itself needs to be an entirely different material, strong enough to protect the wing beneath it but light enough not to weigh down the insect in flight, smooth and aerodynamic to minimise wind resistance, hinged with an actuating mechanism to flip it up and down and programmed to synchronise with the wing folding. If you look carefully you will see the insect closes its wingcases before the wings are completely withdrawn, and the internal surfaces of the case are shaped to assist the process of folding.

If all this came together by accident it would be a miracle!

And a miracle is exactly what it is. A purposeful piece of superb engineering by the great divine Engineer and Creator, exposed for us to marvel at by modern technology, microscopy, high speed photography and the scientists who uncovered it.

What ‘excuse’ do we have to reject such a marvel?

see Romans 1:20

We do not use cookies on this website. We do not collect any of your personal details, and our list of subscribers is not shared with any third party.

Intelligence and purpose in the natural world

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.